In today’s world, the study of history often feels like a science — careful, precise, and endlessly skeptical. It favors records over recollections, footnotes over feeling. A good historian, we’re told, must be dispassionate and detached; more interested in grain yields and archival minutiae than in the moral weight of a single life.

But the thing is, nothing could be farther from the truth. History was never meant to be a science, but a torch, used to light the way forward by the examples of those who came before us.

For most of human history, that’s exactly how it worked. People didn’t study the past to correct it. They studied it to be corrected by it. To be challenged, guided, even inspired.

But somewhere along the way, we lost that fire. We began treating the past like a crime scene: something to analyze, not admire.

So in today’s article, we look to the past to better understand the real meaning of history — and how we can recover what was lost…

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month:

Full-length articles every Wednesday and Saturday

Members-only podcasts and exclusive interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art and philosophy breakdowns

History Begins by the Fire

Before history was ever written, it was spoken. Around campfires, elders recounted stories of their people’s ancestors — hunters, warriors, kings — whose memory lived on not through perfect detail, but through meaning. The stories weren’t designed to inform, but to transform those who heard them.

The boy who listened to how his grandfather saved the tribe from starvation wasn’t taking notes. He was learning what courage looked like. The girl who listened to tales of her mother’s escape from a rival clan wasn’t focused on dates and timestamps. She was being taught resilience.

These stories often blurred the line between fact and legend. But that wasn’t a flaw — it was the point. The story endured because it mattered, which made the facts of it become legend. It bound people to their past, gave shape to their identity, and offered a model for how to live.

Traditionally, the role of the historian was much closer to that of a bard or a priest than a bureaucrat. His task was first and foremost to pass on the values of the tribe — not to verify census data.

Enter the Ancients

When history was finally written down, the spirit of those fireside stories remained.

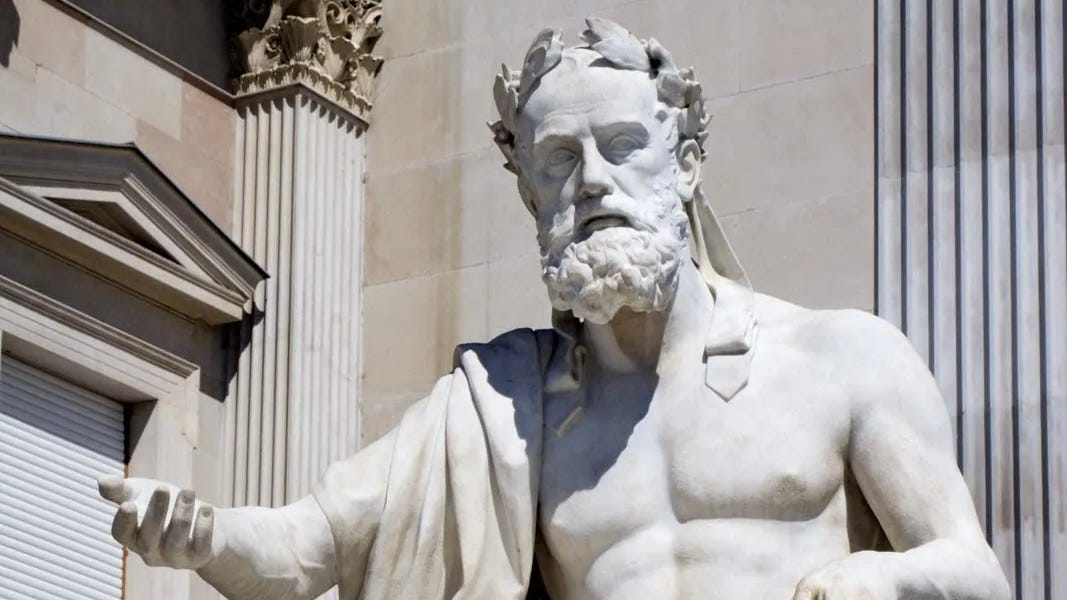

Take Xenophon, for example. A soldier, student of Socrates, and historian of Greek campaigns, Xenophon recorded events not just to preserve them, but to offer examples of leadership and moral character.

In his Anabasis, he puts speeches into the mouths of men — speeches they may not have given word-for-word, but which capture the heart of what they stood for. For the ancients, the essence of what was said mattered far more than the transcript.

The philosopher-historian Plutarch was even more explicit in his aims to teach and inspire. He wasn’t interested in chronicling events for their own sake, but rather wanted to show what kind of men rose to power, what virtues lifted them, and what vices brought them down.

This is why Plutarch composed his Parallel Lives, in which he paired together biographies of different men — not because their timelines overlapped, but because their lives offered complementary or contrasting lessons. For Plutarch, writing was a form of moral instruction. More important to him than the question “what happened?” was the question “what kind of person achieves this, and what can we learn from him?”

None of the ancient writers were reckless with the truth, but neither were they obsessed with precision for its own sake. Crucially, they understood that history was a form of moral memory — and that its value lay not in perfect accuracy, but in lasting insight.

The New (Old) Way Forward

Today, history departments are full of intelligent people doing detailed, technical work — but the moral heart of the discipline is often missing.

Historians correct each other’s footnotes. They question whether someone said a quote that’s been attributed to him for centuries. They write thousands of words about grain prices in 17th-century Spain. But few try to explain why Cicero still matters — or how reading him might make you braver, wiser, and more composed under pressure.

Our culture has grown uncomfortable with the idea that history should inspire. Too many modern biographies treat admiration as naivety — as if any respect for a great man means you’ve failed to see his flaws. But if all we do is dismantle our heroes, what do we offer in their place?

Of course, we should be critical where it’s warranted. The past was not perfect. But neither are we, and that’s exactly why we still need inspiring figures to look to — men and women who faced chaos, took bold decisions, and overcame adversity. People whose lives weren’t neat, but whose stories still shine with insight.

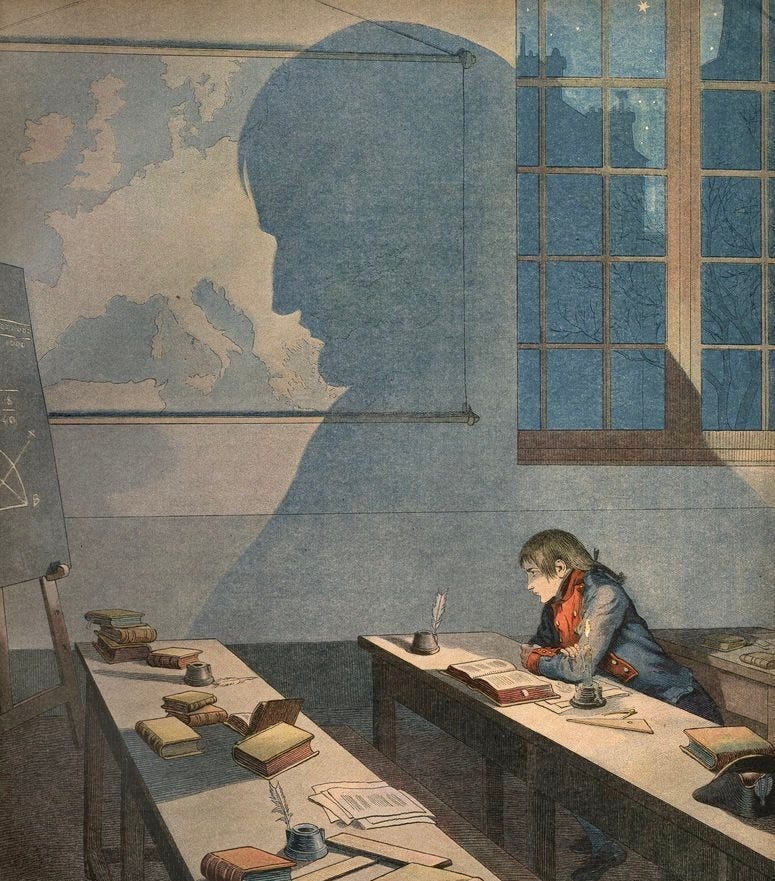

The real questions to ask aren’t “did Napoleon actually say this?” but rather “what kind of vision does it take to reshape the world?” The point of history isn’t to get every detail right. It is to understand human nature, and to live accordingly.

Because ultimately, history isn’t just about what happened — it’s about who we are, and who we might become.

Thanks for reading!

Remember, you can support us and get members-only content every week: great literature, art, and philosophy breakdowns.

This weekend, we dive into the world of JRR Tolkien, and explain why his Middle-earth is so deeply attractive to modern readers.

Tolkien's world-building wasn't just an act of fiction writing, but of something he called "sub-creation"...

This is great! As a history teacher at a classical Christian school this is constantly my aim! My 7th and 8th graders are just finishing a thesis making an argument for what made a good Roman. They had to look at all the individuals we studied throughout the year and give evidence for the most common moral virtues. Within the paper they had to include an argument as to why these virtues are still something to strive for today.

Sending this to everyone who asked why I majored in history at university 🥹 thank you!